Every morning, millions of American children walk into schools struggling with limited resources, while just a few miles away, their grandparents receive government checks that have never missed a beat.

This disparity isn’t because children are any less in need. Rather, it reflects a political and systemic imbalance — one that guarantees steady support for retirees but leaves funding for children subject to constant debate.

An Urban Institute analysis found that in 2023, the government spent over $37,000 per senior, compared to just $7,300 per child under 19 — a ratio of roughly 5-to-1. Although this gap briefly narrowed during the COVID-19 pandemic, it has since stabilized, and recent policy proposals suggest it’s unlikely to shrink anytime soon.

“We haven’t shifted gears,” said Eugene Steuerle, former Treasury official and co-founder of the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, in an interview with Newsweek. “Most of the growth in spending has gone to retirement and healthcare, while programs that promote upward mobility—like education, housing, and early childhood support—have been left behind.”

Steuerle explains that government spending has become largely automatic, with Social Security, Medicare, and interest payments dominating the federal budget. Everything else—child care, education, infrastructure—must fight over the leftovers. He calls this the death of “fiscal democracy.”

“Both parties are stuck,” he says. “Republicans resist raising taxes on the wealthy, while Democrats fear slowing the growth of Social Security or healthcare.”

Not everyone agrees that seniors are draining resources from younger generations—least of all seniors themselves. In response to a 2024 New York Times op-ed by Steuerle and journalist Glenn Kramon titled “Young Americans Can’t Keep Funding Boomers and Beyond“, readers defended Social Security and Medicare as earned benefits, paid for throughout a lifetime rather than handouts.

“Without Social Security, nearly 40 percent of seniors would fall into poverty. Before Medicare, most had no health coverage,” wrote Max Richtman, president of the National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare, along with former Senator Tom Harkin, in a letter to the Times. Other readers pointed out that baby boomers contribute significantly by providing child care, volunteering in their communities, and supporting their adult children financially—often while struggling themselves.

Younger Americans, however, argue that even if today’s retirees earned their benefits, the financial landscape has changed dramatically. A ConsumerAffairs analysis reveals that while purchasing power is higher than in the 1970s, the cost of essentials has soared: home prices have increased by over 1,000 percent, public college tuition by 177 percent, and rents by more than 50 percent. Meanwhile, wages have failed to keep pace, leaving many younger adults feeling like they’re paying more into the system while having fewer resources to build their own financial security.

In 2024, approximately $4.1 trillion in federal spending was allocated to mandatory programs like Social Security and Medicare, making up nearly two-thirds of the total budget. In contrast, discretionary spending—which funds education, child care, infrastructure, and workforce programs—accounted for about $1.8 trillion.

The country faces a growing fiscal stalemate. Since the 1980s, about 80 percent of the increase in domestic spending has been directed toward entitlement programs, according to federal statistics. This trend is expected to continue as baby boomers retire in larger numbers and live longer lives. Notably, in 2024, interest payments on the national debt exceeded defense spending for the first time, totaling $881 billion. This challenge is worsened by a broader trend: the national debt has grown to four times its size relative to GDP since 1980.

Maya MacGuineas, president of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, warns that younger generations are already feeling the pressure, describing the budget’s priorities as “upside-down.” “The government spends six dollars on seniors for every one dollar spent on children under 18. Meanwhile, seniors experience the lowest poverty rates, while children face the highest,” she told Newsweek.

“This inverted budgeting approach signals trouble ahead for the nation on many levels.”

Funding for children’s programs is already shrinking. The Urban Institute forecasts that by 2034, spending on children will decline to just 1.9 percent of GDP, down from 2.4 percent in 2019. Almost every area—including education and tax credits—is expected to see cuts. The only exception is health care, though even that growth depends heavily on Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which could face reductions under current budget plans.

While Donald Trump’s second administration inherited these fiscal challenges, its “One Big Beautiful Bill” package increases tax breaks for retirees but leaves funding for children’s programs flat or reduced. Analysts from the Urban Institute estimate that federal investment in children could decrease by as much as 20 percent of GDP over the next decade, even as the economy grows.

Some conservative proposals take even more drastic steps. For instance, Project 2025 suggests cutting Head Start, a program that offers early education to over 800,000 children. Meanwhile, the Republican Study Committee’s budget plan aims for significant reductions in Medicaid, SNAP, and CHIP funding.

The Urban Institute cautions policymakers to think carefully before trimming these essential programs in the name of efficiency, emphasizing the long-term risks of neglecting investments in children.

The divide between generations in government spending isn’t just about who gets more. Many retirees are drawing benefits they’ve earned, but the system itself is structured in a way that puts younger workers at a disadvantage.

Payroll taxes meant for Social Security and Medicare don’t accumulate in a fund for future retirees; instead, they are paid out immediately to current beneficiaries. A typical couple retiring in 2025 with average earnings is expected to receive about $1.34 million in lifetime benefits, despite having contributed only $720,000 in today’s dollars. This gap more than $600,000 is effectively covered by the working-age population.

Eugene Steuerle, a former Treasury official, notes that most growth in government spending has gone to retirement and healthcare programs, leaving those that support upward mobility behind. The ratio of working adults to retirees has fallen drastically—from over five workers per retiree in 1960 to fewer than three today—and is projected to drop to around two by 2035. The shrinking workforce funding these programs contrasts with a growing number of retirees.

Despite this, entitlement benefits continue to increase automatically. Without legislative action, the Social Security trust fund could begin to deplete as soon as the early 2030s, potentially forcing cuts of up to 20 percent across the board. Yet, attempts at reform remain politically sensitive, with lawmakers focusing on protecting current retirees rather than rebalancing for future ones.

Maya MacGuineas of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget emphasizes the need for substantial budget changes that both safeguard seniors and invest in the future.

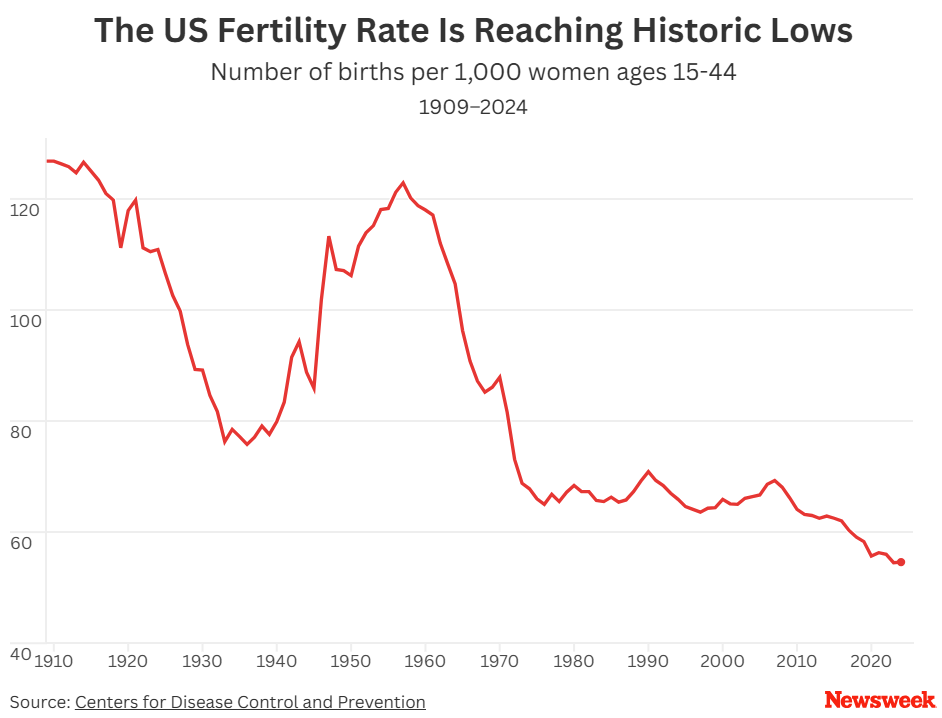

Beyond fiscal challenges and fairness, there’s a demographic crisis: the U.S. is facing a declining birth rate. In 2023, the fertility rate fell to a record low of 1.6 births per woman, well below the 2.1 rate needed to sustain the population. This trend isn’t due to a lack of desire for children; many younger adults want families but feel financially unable to support them.

Surveys reflect this conflict. A 2023 Gallup poll found nearly half of Americans believe an ideal family has one or two children, with just 2 percent supporting having none. Yet a Pew survey that same year revealed that 47 percent of adults under 50 who don’t have children say they likely never will. Among them, around 60 percent say they simply don’t want children, while nearly 40 percent cite financial concerns or pessimism about the future as reasons to avoid parenthood.

Beth Jarosz of the Population Reference Bureau explains that Americans recognize the challenge lies in lacking support to have as many children as they want—whether that means none or several. Steuerle points to policy as a root cause, saying, “We encourage young people to have kids, but we’ve made it harder for them to buy homes, secure good jobs, and raise families.”

Recent economic trends reveal a dramatic shift in wealth distribution. In 1989, individuals aged 35 to 44 controlled nearly 75% of the assets held by those aged 65 to 74. Fast forward to 2022, and that proportion has fallen to about one-third. Homeownership, long a symbol of middle-class stability, is becoming increasingly out of reach. At the same time, student loan debt has surged to unprecedented levels—debt that cannot be wiped out through bankruptcy—leaving many young adults burdened by loans for degrees that no longer guarantee financial security.

“Many young people don’t complete college, and those who do often carry heavy debt with little return,” explains Steuerle. “We’ve set up a misleading narrative that college is the answer for everyone, without providing adequate alternatives for those who don’t finish.”

Proposed solutions vary and are often short-lived. Ideas such as Trump’s “baby bonus” and JD Vance’s suggestion to enhance voting rights for parents have sparked debate but failed to gain lasting traction. While Democrats support higher taxes on the wealthy and profitable corporations, experts at the Urban Institute caution that this approach won’t fully address the growing financial demands.

One debated strategy among policymakers is increasing immigration to compensate for declining birthrates and maintain the workforce necessary to support programs like Social Security and Medicare. A 2024 article in The Lancet highlights that immigration will become critical for sustaining economic growth in countries with low fertility rates, including the U.S. However, immigration policies have tightened, particularly under the Trump administration, even as the population ages and birthrates decline.

“We’re operating a modern economy with outdated commitments,” Steuerle observes. “The generation funding these promises wasn’t even alive when they were made.”

Read full article here: News Week.